Wealth effect and its implications on housing consumption

In a study that uses ex post empirical data over a period exceeding two decades, Ying Fana and Tien Foo Singb find evidence of conspicuous consumption of housing in Singapore by Chinese foreign buyers after experiencing positive wealth effect.

17 September 2021

What happens when people become affluent? Do they consume more of the same, or will their consumption patterns change? Will they continue eating hamburgers at fast-food joints in greater quantities or will they perhaps contemplate prime steak at a fancy restaurant?

Economic theory suggests that consumption patterns will alter as people move across the spectrum from inferior and normal goods to indulge in discretionary and luxury items. German statistician Ernst Engel, known for the Engel curve and Engel’s law, found that as household income increases, the proportion spent on food and other subsistence necessities decreases, while that spent on education, health and recreation increases.

Thorstein Veblen, an American economist and sociologist, coined the term “conspicuous consumption” to describe deliberate expenditure on luxury goods, primarily to signal wealth and status in a bid to gain one-upmanship over other members of the social circle.

Wealth effect and conspicuous consumption of housing

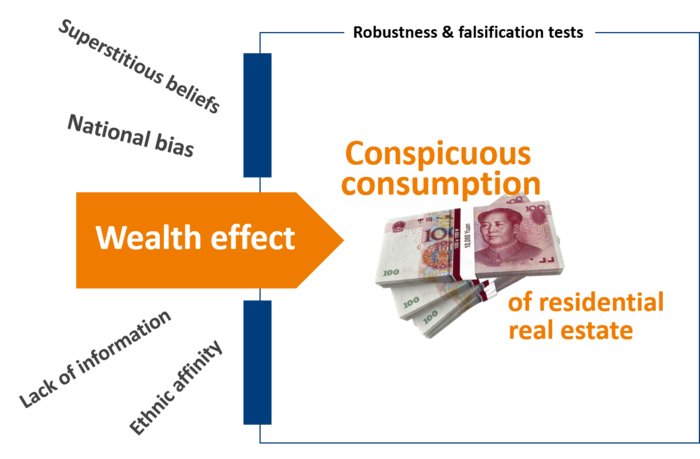

In their paper “Macroeconomic policy-induced wealth effects on Chinese foreign housing investments”, Fan and Sing (2021) find evidence of conspicuous consumption of residential real estate in Singapore by Chinese foreign buyers who had experienced wealth effect.

On 21 July 2005, the People’s Bank of China announced a major reform to the exchange rate regime by unpegging the Chinese yuan (or renminbi, RMB) from the US dollar (USD), and then transiting to a floating exchange rate regime based on market supply and demand with reference to a basket of currencies (hereinafter, the “policy shift”).

The policy shift resulted in an appreciation of the RMB relative to the USD and Singapore dollar (SGD) as well. What that meant was that Chinese consumers – specifically Chinese foreign buyers of housing in Singapore – now had stronger purchasing power.

Would they buy more housing, or would they instead go for residences such as penthouses, high-floor units and large apartments that signal wealth and status (i.e. conspicuous consumption)?

Experimental design

The wealth effect arising from the policy shift affects only Chinese foreign buyers, whereas foreign buyers of other nationalities remain status quo. In this regard, the policy shift, in Fan and Sing’s experiment, is an independent variable that represents a “clean” exogenous shock that affects the housing consumption behaviour of Chinese foreign buyers. It adds evidence to a body of knowledge that previously had to contend with “endogeneity concerns”, such as difficulty with isolating the effects of independent variables and factoring out “noise” from other unknown variables that may have confounded experimental results.

To isolate the effects of the policy shift on consumption behaviour, Fan and Sing had Chinese foreign buyers as the treatment group and other foreign buyers (Indonesians, Malaysians etc.) as the control group. The researchers then applied the Differences-in-Differences (DID) methodology in multiple linear regression analyses to measure pre- and post-policy behaviours in both groups.

Findings

Findings showed that Chinese foreign buyers had a greater propensity to pay more than their counterparts of other nationalities. Specifically, Chinese foreign buyers were willing to pay more per square metre of floor area (as opposed to absolute sale value) than their counterparts for comparable housing types.

This willingness to pay a higher price per unit floor area is interpreted by the researchers as indicating conspicuous consumption (as opposed following the Engel function, which would entail purchasing more housing). Prior to the policy shift, Chinese foreign buyers, on average, paid a marginal 0.63% more than other foreign buyers per unit area, but this differential jumped substantially to 3.42% post-policy shift.

To obtain more supporting evidence, Fan and Sing further examined the treatment group’s preference for “signalling” attributes, defined in the study as “high-floor unit”, “large unit” and “expensive unit”. While Chinese foreign buyers tended to be more conservative relative to other foreign buyers prior to the policy shift, their behaviour however changed after 2005 – demand from the treatment group increased by 2.37% for high-floor units, 3.34% for larger units and 5.91% in the more expensive segment of housing markets.

Fan and Sing next moved on to examine the extent to which the treatment group was willing to pay for the aforementioned signalling attributes.

A comprehensive database, comprising nearly 19,000 transaction records by foreign buyers from 1995 to 2017, gave the researchers ample leeway to investigate the purchasing behaviours of buyers with diverse profiles, and then compare them against one another, for example:

- Chinese vs non-Chinese

- Chinese, pre-policy shift vs post-policy shift

- Pre- and post-policy shift for both treatment and control groups

- Chinese buyers with preference for signalling attributes versus Chinese buyers looking for housing in general, and etc.

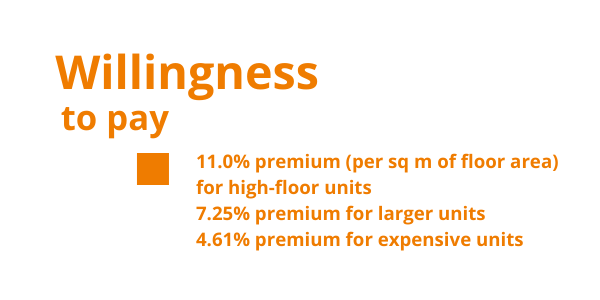

After drilling down to post-policy shift in Chinese foreign buyers’ preference for signalling attributes, results showed that this group paid an 11.0% premium (per sq m of floor area) for high-floor units, 7.25% premium for larger units and 4.61% premium for expensive units compared to the control group of other foreign buyers.

Taken in conjunction, the three findings of post-policy shift Chinese foreign buyers:

- paying a higher price per unit floor area,

- exhibiting greater demand for signalling attributes (high-floor, larger units, more expensive), and

- willingness to pay more for all three signalling attributes,

jointly make a case for the conspicuous consumption of residential real estate triggered by the 2005 policy shift.

The hypothesis receives further corroboration when conspicuous consumption motives were augmented in high-income neighbourhoods and neighbourhoods with strong enclaves and social networks comprising residents from China. Additionally, signalling motives were more significant for Chinese foreign buyers who were owner-occupiers than for investors, who would presumably be more interested in returns-on-investment than status and prestige.

Competing explanations and theoretical implications

Through a series of robustness and falsification tests, the study ruled out the possibility that the treatment group’s willingness-to-pay was linked to other factors such as national bias or ethnicity affinity, local knowledge disadvantage or superstitious beliefs. The researchers also showed that conspicuous consumption motives were not triggered by immigration or the safe haven motives of Chinese foreign buyers.

By ruling out competing explanations and therefore other independent variables that may affect housing consumption patterns, Fan and Sing make a case for a causal relation between the two phenomena under study. Considering that wealth effects were temporally prior to conspicuous consumption, and until new evidence to the contrary surfaces, we can accept the proposition that wealth effects causes the conspicuous consumption of housing.

Fan and Sing’s study thus value adds to earlier research in this area, but which were inconclusive with respect to the magnitude and the causal direction of the housing wealth effects due to issues with endogeneity.

At the broader level, their research is related to the transmission of wealth shocks to international housing markets and indirectly adds evidence to the literature on financial liberalization and foreign capital flows.

a Department of Building and Real Estate, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China

b Institute of Real Estate and Urban Studies and Department of Real Estate, National University of Singapore, 21 Heng Mui Keng Terrace, 119613, Singapore