How do developers respond to the ABSD?

Diao, Fan and Sing (2021) investigate developers’ pricing strategies in response to ABSD measures, and examine how this ABSD policy brings welfare gains for homebuyers.

11 October 2022

In an unlikely scenario where land were privately held, owners may just release their land in trickles, ensuring demand outstrips supply at any given time. Prices will skyrocket as homebuyers engage in a frenzied rush for a very limited amount of housing.

While the above could possibly happen in a laissez-faire economy without an independent government to balance things out, in reality, most markets will have some macroprudential policies to regulate irrational activities.

In Singapore, macroprudential measures, such as the Total Debt Servicing Ratio (TDSR) and Loan-to-Value (LTV) ratio, are targeted at controlling credit availability for buyers. Transaction taxes, including the Additional Buyer’s Stamp Duty (ABSD), are also imposed to curb demand in overheating markets.

To discourage developers from hoarding land, the Government also imposes an ABSD on developers for all land acquired, which was first introduced on 8 December 2011. With this new measure, developers who failed to develop and sell all housing units within a 5-year window would have to pay an ABSD of 10% of the original acquisition price with accrued interest. The ABSD rates imposed on developers have been raised three times, increasing from 15% and 30% in 2013 and 2018 respectively, to 40% (inclusive of a 5% non-remissible portion) after December 2021.

How do developers respond to ABSD?

Using the 2011 ABSD as an exogenous shock, Diao, Fan and Sing – in their paper published in the Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization (2021) “Rational pricing responses of developers to supply shocks: evidence from Singapore” – investigated whether developers responded rationally. They examined whether developers cut prices in the 5th year in a bid to sell off balance units and thereby avoid the ABSD penalty.

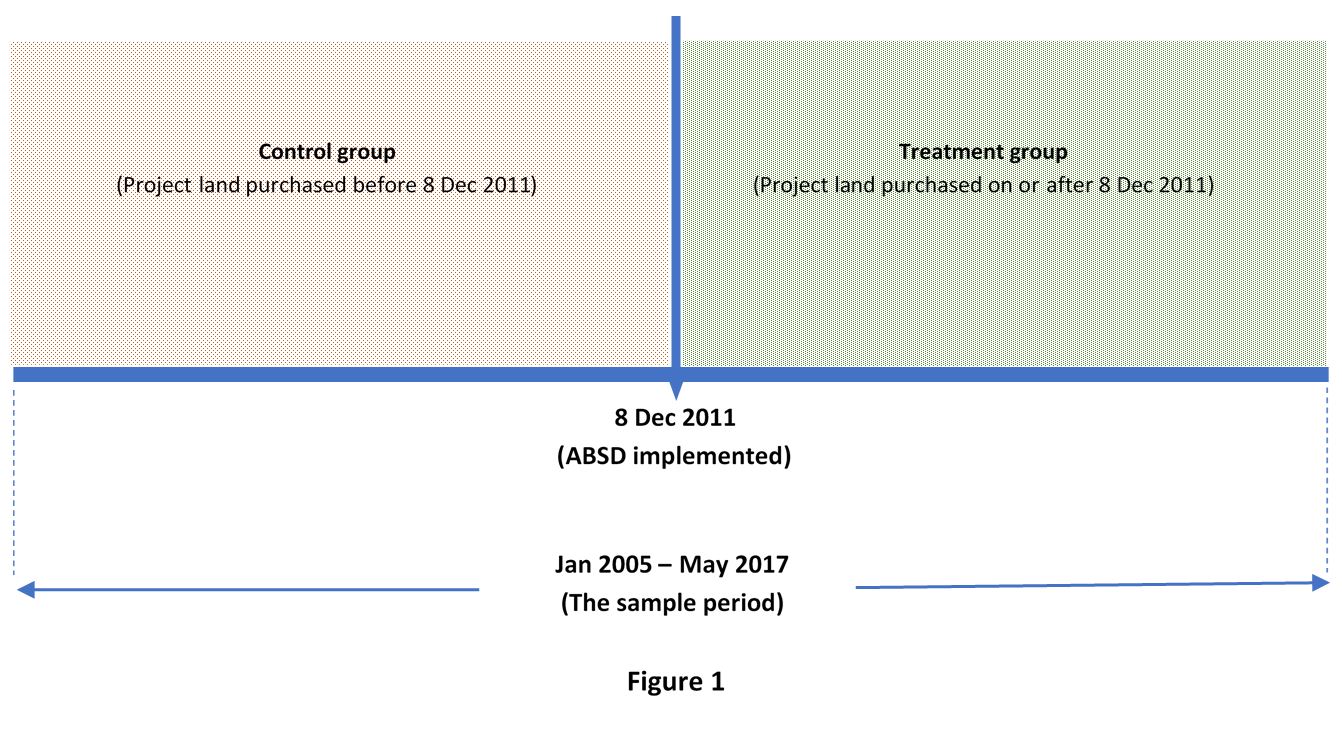

In the difference-in-differences (DID) experimental design, the treatment group comprised developers who acquired land on or after 8 December 2011, while the control group comprised those who made their purchases earlier.

Empirical data spanning January 2005 to May 2017 (the sample period) were obtained from three main sources, namely, (1) residential land sales from the two government-appointed land sales agencies – the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) and Housing Development Board (HDB); (2) en bloc sales of private residential projects with redevelopment potential (brownfield sites); and (3) new non-landed private housing sales from the Real Estate Information System (REALIS) of URA (Figure 1).

A total of 93,126 transactions were identified for observation, with 39,366 transactions under the treatment group and the balance of 53,760 transactions categorised into the control group.

Findings

The baseline regression analysis results indicate a significant and negative coefficient of -0.028. The results imply that developers of the treatment projects that were subject to the ABSD offered a price discount of 2.8% for units launched in Year 5 relative to the control projects sold in the same year (see the Appendix for the detailed empirical design).

The study also compares only within the ABSD-affected projects by comparing properties sold in the first three years with those in Years 4 and 5. Compared to this new reference group, 5th-year discounts decreased but remained at a statistically significant 1.8%. However, Year 4 properties were marked up by an average of 4.6%, suggesting that developers were trying to maximize profits before attempting to divest all units in Year 5.

As robustness tests, the researchers excluded projects launched after 2013, since the sample period which ended in 2017 would not be able to capture the 5th year of these projects (i.e. 2018). The regression coefficient returned the same value of -0.028, which supported the baseline regression in that it had not included any non-Year 5 data in the original analysis. This also indicates a database that is relatively clean of errors.

The increase in discounts appeared to be attributable to the treatment group’s proximity to the ABSD: the policy shock triggered stronger responses from developers in projects launched in the first two years after the ABSD.

Welfare gains and tax savings

Based on the number of Year-5 units sold over the sample period (estimated to be collectively worth S$1.16 billion) and an estimated average discount of 2.8%, Diao et al. computed S$32.5 million worth of discounts given to homebuyers.

Assuming that the hedonic attributes of Year 5 units have not changed over time, homebuyers enjoy the same value for their purchases. Yet, an overall welfare gain of S$32.5 million is obtained, which could be consumed, saved or invested.

From the developer’s perspective, the revenue loss arising from cutting prices for Year 5 sales could still be lower than the ABSD penalty – which was 10% of the land costs with accrued interest. Diao et al. estimated the ABSD savings for developers, which would otherwise have been incurred if they failed to sell all their units, to range from S$9.4 million to S$176.8 million.

Viewed from such a perspective, the ABSD policy is not a zero-sum game where the homebuyer wins and the developer loses, or vice versa. The ABSD is a fiscal tool that addresses a potentially negative externality from land hoarding. This, as the premise, subsequently helps market players derive welfare gains and tax savings.

Authors:

Mi, Diao is a professor at the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University, Shanghai, China.

Yi, Fan is an assistant professor in the Department of Real Estate, NUS Business School, National University of Singapore.

Tien Foo, Sing is a professor of real estate and Director of the Institute of Real Estate and Urban Studies (IREUS) at the National University of Singapore.