Liberalising home-based business and its welfare outcomes

A study of Singapore’s Home Office Scheme (HOS) finds evidence for a causal relationship between the HOS and the creation of new businesses.

2 June 2022

Covid-19 has radically changed how work and business are done. By unleashing an unprecedented disruption on commuting and office-based activity, the pandemic has fast-tracked the work-from-home and work-from-anywhere phenomena, which have, in turn, catalysed interest and demand for operating home-based businesses.

Entrepreneurship has long been recognised as a contributing factor to innovation, job creation and overall economic growth. With more people now ready to accept the home as a venue for income generation, how then should policymakers respond?

In their paper “Liberalizing Home-Based Business”, Agarwal, Sing, Song and Zhang (2021) study the Home Office Scheme in Singapore that allows business to be conducted on residential premises and the Scheme’s impact on entrepreneurial activity.

Through a series of regression analyses, the researchers showed that the Scheme encouraged the formation of new businesses, and that firms created in response to the HOS enjoy a higher survival rate. The HOS had attracted more entry into self-employment without compromising the average quality of the pool.

The study highlights the importance of encouraging home-based commerce, and can inform policymaking on further liberalisation of the cottage industry as policy implications.

The home-based entrepreneurship scheme

In November 2001, the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) launched a pilot home-based scheme that allowed small-scale businesses to operate from homes in selected mixed zone areas. In collaboration with the Housing & Development Board (HDB), the Scheme was subsequently expanded and formally designated as the “Home Office Scheme” in June 2003 to include all residential units in Singapore.

Experimental design

While identifying businesses eligible for the HOS, the Scheme also stipulated a negative list of industries prohibited from home-based operations.

The former segment, comprising businesses like computer programming, office support and financial services, is assigned to the treatment group, while the latter, which included construction, food catering and retail trade, is assigned to the control group since they were excluded from the HOS. The policy stance was that home-based businesses should not cause disturbance to the residential neighbourhood.

As the HOS is an exogenous intervention at the launch time, the researchers could therefore adopt a standard difference-in-differences (DID) approach to evaluate the impact of the HOS on the outcome variable, which in the context of the study, was defined as the logarithm of the number of new businesses created per month.

The researchers deployed propensity score matching – involving parameters like productivity, risk, firm size and capital – to construct a matched sample of the treatment and control groups with similar attributes. This served to reduce any selection biases that may have inadvertently resulted from policy criteria.

Data from January 1999 to March 2005 (the “sample period”) were used in regression analyses. The sample period was delimited in such a manner to avoid the confounding effect of the 1997–1998 Asian financial crisis, and Singapore’s Limited Liability Partnership Act implemented in April 2005. The data sources were business registry data obtained from the Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority (ACRA) and a proprietary personal database containing demographic information of more than 2 million people in Singapore.

Validating the DID

A key premise underlying the DID approach is the “parallel trend” assumption that in a counterfactual scenario where there was no exogenous intervention, the difference between treatment and control groups would display similar patterns on the outcome variable.

After running a regression analysis between the treatment and control groups for the period before the Home Office Scheme, Agarwal et al. found a small and statistically insignificant difference of 2.4 percentage points between the two groups.

In contrast, firm creation grew by a substantial 23 percentage points more following the reform for the treated industries than the control group. After controlling for industry-specific factors, time variables and macroeconomic conditions, the regression coefficient measuring the HOS impact remained statistically significant, ranging between 21.1 and 23.8 percentage points.

The negligible difference during the pre-treatment period, juxtaposed with a significant divergence between the two groups during the treatment period, suggests that the study’s DID approach was valid. There could be a causal relationship between the HOS and new business creation.

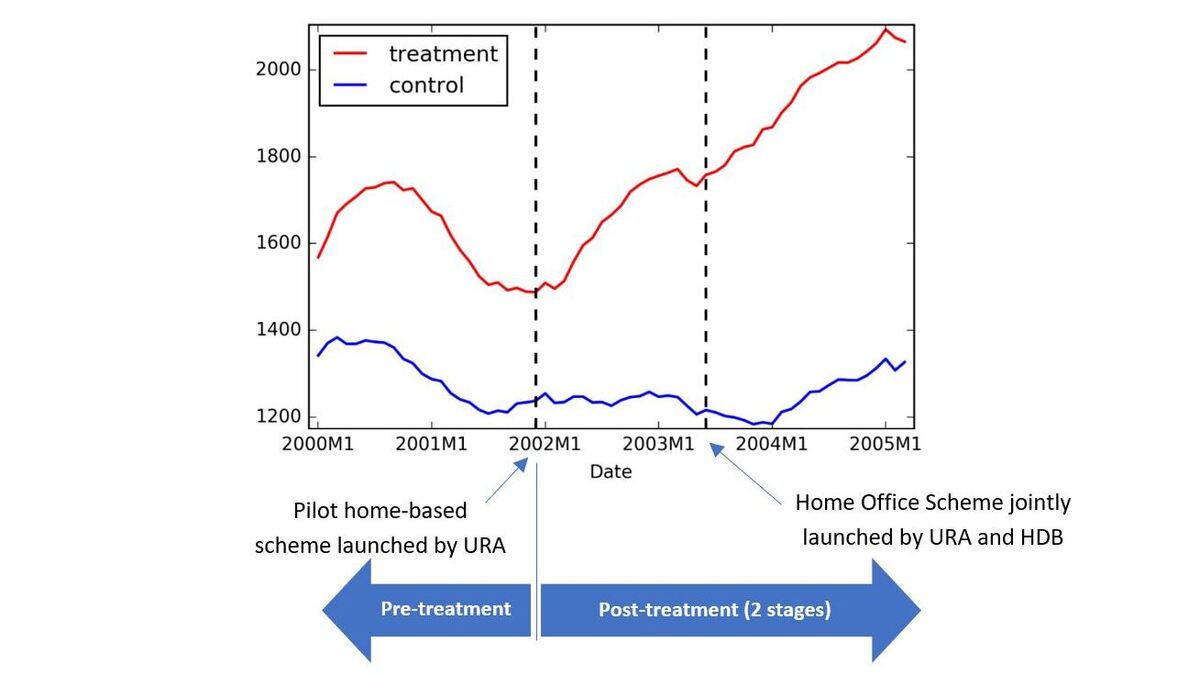

Figure 1: Business creation – treated vs control

Further evidence for causality

To further establish the hypothesis that the HOS increased creation of new businesses, Agarwal et al. conducted a series of robustness tests.

(i) Geographical variation during stage 1

At the outset (from Nov 2001 to May 2003), the home-based business programme piloted only in selected areas. The researchers therefore compared firm creation for the same industry in selected areas against those that were not selected, with the latter serving as the control group. Results ranged between 12.8 – 14.4 percentage points and were statistically significant.

(ii) Extensive margin during stage 2

Given that the programme was expanded to apply to all residences countrywide from June 2003, it would follow that business creation would escalate during the second stage. Results from regression analyses corroborated this expectation and showed that the treatment group exceeded the control group by between 30.7 – 32.6 percentage points, depending on the extent of controls deployed (see Figure 1 above for illustration of increased divergence).

(iii) Other robustness tests

After drilling down to firms with registered office addresses that matched residential addresses, the researchers found a divergence between treatment and control groups ranging between statistically significant 17.2 – 21.2 percentage points. Regression, weighted by industry, was also performed to rule out the possibility of small business sectors exerting a disproportionate effect on the overall statistics.

Agarwal et al. further conducted a falsification test, in which firms were assigned at random into the treatment and control groups. The premise here is that randomisation would effectively undo any correlation between the test variables, failing which the original hypothesis would be falsified since the correlation could now be due to an unknown variable as yet undiscovered by the study. Regression coefficients produced by the falsification test were statistically insignificant from zero (which indicates no correlation). They, therefore, supported the original hypothesis that the Home Office Scheme had a causal impact on business creation.

Who benefitted most from the Scheme?

Study results indicated that the effect of the Home Office Scheme was more pronounced for low-income households, female individuals and industries requiring high start-up capital. These findings suggest that reducing entry costs was important to encourage firm creation and that non-pecuniary benefits, which allowed for balancing between business activity and household responsibility, encourage female individuals to enter the market.

Policy implications

The exit rate of newly created firms after the HOS decreased by 29% relative to comparable start-ups in the control group. Before the reform, new firms in treated industries were 1.6% more likely to exit than those in the control group: however, start-ups induced by the reform exhibited a lower cessation rate of 22.4%

In so far as survivability is a measure of firm quality, study results suggested that the Home Office Scheme had improved the quality of new businesses created under the programme. Plausible explanations for this outcome include lowering operational overheads, which help firms survive with low cost, and possibly channel savings back into the business for further investment and growth.

The liberalisation of home-based business here in Singapore has achieved a twofold objective of encouraging entrepreneurship and improving the quality of firms.

Authors:

Sumit Agarwal is the Low Tuck Kwong Distinguished Professor at Business School and Professor of Economics, Finance and Real Estate at the National University of Singapore.

Sing Tien Foo is a Professor, Head of Department of Real Estate, Business School and Director of the Institute of Real Estate and Urban Studies at the National University of Singapore.

Song Changcheng is an Associate Professor of Finance at the Lee Kong Chian School of Business at Singapore Management University.

Zhang Jian is an Assistant Professor of Finance at the University of Hong Kong Business School.