How to convince people to save electricity?

Campaigns persuading consumers to save energy have demonstrated a tendency to fall on deaf ears, but monetary motivation appears to be effective.

25 February 2022

Would you turn off your air-conditioner to conserve energy and save the Earth? In Singapore's sultry, tropical climate, you'll get all sweaty though.

The trade-off between personal comfort for a long-term social cause is a dilemma that everyone must grapple with, and research has suggested that people – rather unfortunately – tend towards personal gratification. Mass media campaigns on climate issues conducted in Japan and the Netherlands some years back created public awareness but did not have lasting effects. Such an outcome is hardly surprising, since the responsibility to save the Earth is diffused over nearly 8 billion people worldwide.

But what if campaigns also factored in financial benefits, for example, in the form of household costs savings? Would the rational economic individual now act with clear intent and sustained purpose?

In their paper "Public Media Campaign and Energy Conservation: A Natural Experiment in Singapore", Agarwal, Sing and Sultana (2022) investigate the effectiveness of Singapore's energy campaigns in catalysing desired behaviours in the local population. Specifically, they studied campaigns run by the National Environment Agency (NEA) in collaboration with Town Councils (the municipal authorities in Singapore) from January 2016 to June 2016.

Save energy, save money

In a public campaign involving 52 randomly chosen hawker centres spreading across the island and more than 6,000 residential (or "HDB") blocks housing more than one million residents, the NEA put up banners and posters with an eye-catching headline of "SAVE ENERGY SAVE MONEY" on hawker-centre premises for the period January 2016 to June 2016.

Hawker centres are open-air complexes with a collection of stalls selling various cooked food. With few exceptions, such as those located in business districts, hawker centres are mostly located within housing estates and are popular venues for residents to gather for meals. In Singapore, it is common for families to eat out at hawker centres at least 3 to 4 times a week at the hawker centres near their homes.

In addition to information on energy conservation methods, NEA's publicity materials were forthcoming on the associated cost savings. For example, a sample message used included: "switching off the power sockets when not in use could help save up to $25 a year or buying an air-conditioner and refrigerator with 3 ticks (energy-efficient appliances) will help save $350 and $75 a year, respectively."

Experimental design

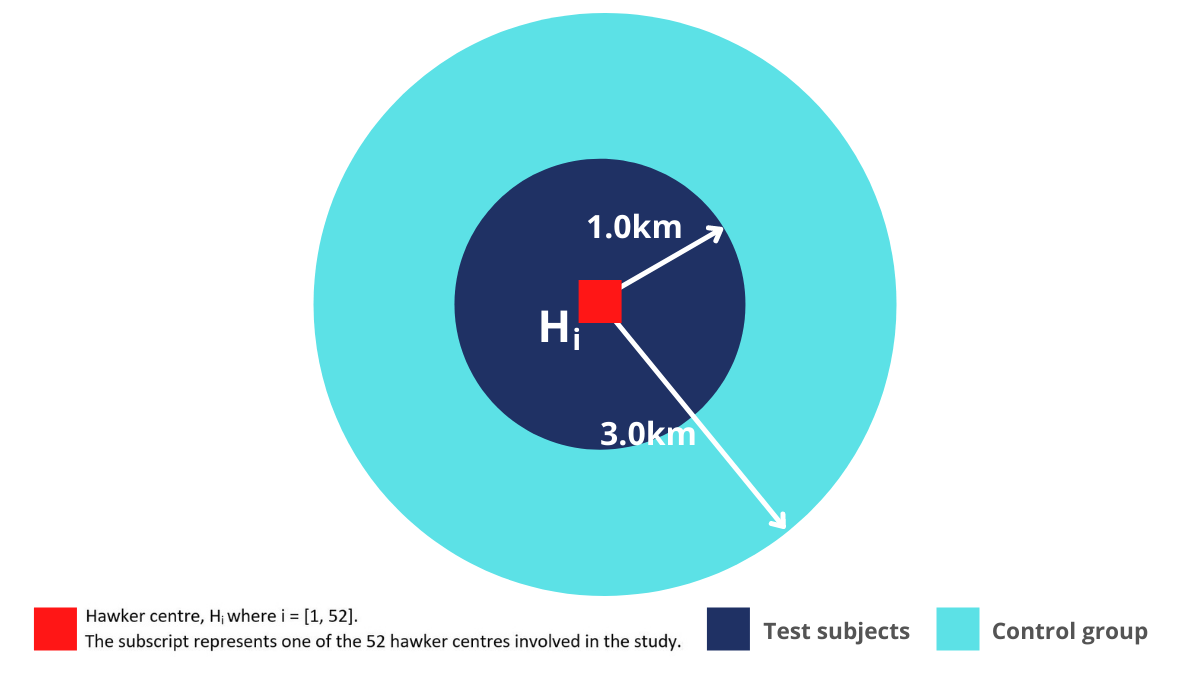

(i) Treat Group (1.0km)

The study covered residents living within a 3-km radius of selected hawker centres, sorted into a treatment group – "Treat Group (1.0km)" – located within a 1-km radius from the hawker centre. Residents in the zone ranging between 2km and 3km of the hawker centre made up the control group (Figure 1). Given the greater distance from the hawker centre, the researchers assumed that the frequency of visits by people in the control group would be substantially lower or nil.

Agarwal et al. additionally investigated the two experimental groups before NEA's campaign. They found that both groups had similar electricity consumption patterns, which meant that the publicity campaign would be an exogenous intervention that could effectively test for changes (if any) in consumption behaviour.

Employing a difference-in-differences (DID) approach, the researchers also studied consumer behaviour around non-participating hawker centres, and found no meaningful change in energy usage during the intervention period. This finding addresses endogeneity concerns and furnishes more confidence that the NEA campaign was an exogenous variable.

Figure 1: Treat Group (1.0km)

Results showed that the treatment group consumed 0.4% less electricity on average than the control group. This result was statistically significant at the 1% level, meaning that the differential being due to random chance was highly unlikely.

Agarwal et al. thus accepted that NEA's intervention had an effect, which resulted in energy savings amounting to 0.4% on average.

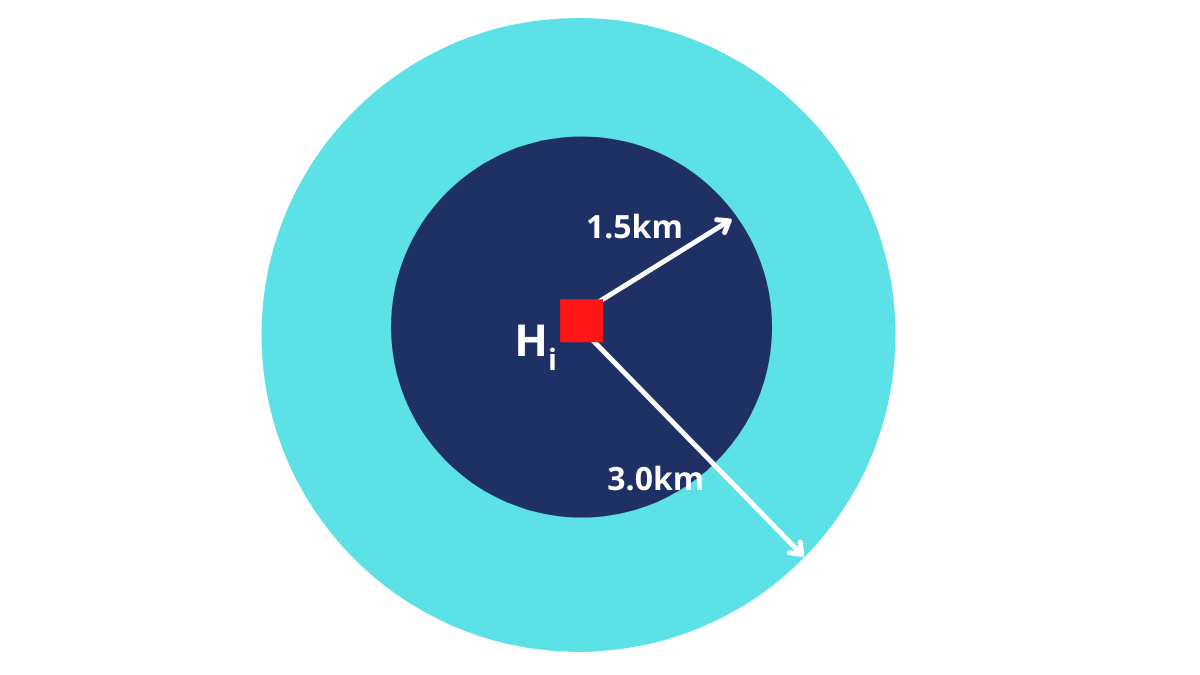

(ii) Treat Group (1.5km) and threshold of effectiveness

The researchers replicated the experiment, but with the locus of treatment extended to 1.5km of a hawker centre, and the control buffer zone shrunk to between 1.5km and 3km away from the venue.

Figure 2: Treat Group (1.5km)

In this replication, the treatment group – "Treat Group (1.5km)" – showed a negligible (0.008%) reduction in energy consumption, and the differential was not statistically significant.

The average energy consumption of residents within a 1km radius had likely been pulled upwards by those living within the 1km – 1.5km zone, such that the combined average did not diverge sufficiently from that of the control group to warrant statistical significance. The effect of the intervention had been diluted to such an extent that Treat Group (1.5km) seemed no different from the control group.

Results from Treat Group (1.0km) and Treat Group (1.5km) considered in tandem suggest that the effectiveness of NEA's campaign had a maximum locus of 1.0km, and this finding would be useful in informing future publicity campaigns.

Savings quantified and post-treatment effect

As a result of NEA's energy conservation campaign, an average of 0.4% of electricity consumption was saved during the intervention period, translating into nearly S$350,000 in dollar terms.

After the industrial and commercial sectors, households are the third-highest consumer of electricity, so this energy market segment holds great potential for conservation and sustainability.

Agarwal, Sing and Sultana's study also demonstrates that interventions which communicated economic gains clearly were more effective than those that did not.