The opportunity cost of using cash and the real impact of mobile payment technology

Agarwal, Qian, Ren, Tsai and Yeung (2020) investigate how mobile-payment channels can positively impact the economy when used as a substitute for cash.

Wong Wei Chen

9 April 2024

While Singapore is increasingly adopting electronic payment technologies, with the Covid-19 pandemic giving further impetus towards a cashless society, cash retains a sizeable role in everyday life, especially among the unbanked and seniors who might struggle to keep up to speed with technology.

According to 2022 figures furnished by Statista, offline cash usage in Singapore amounted to 19% (or nearly one-fifth) of all payment transactions at physical points-of-sale such as retail outlets and restaurants. In comparison, leading cashless nations like China, Sweden, and South Korea ranged between 8% and 11%.

Using cash in commerce entails costs, both for businesses and consumers. Firms handling physical money may have to pay processing fees charged by banks and at the same time expend manhours on counting, storing and securing cash. Individuals, on the other hand, have to contend with the security risks and inconvenience of carrying large amounts of cash, and may additionally miss out on rewards programs and promotions offered by e-payment providers.

To the extent that they hinder commerce, such transactional frictions represent an opportunity cost arising from the usage of physical money. In their working paper “The Real Impact of FinTech: Evidence from Mobile Payment Technology”, Agarwal, Qian, Ren, Tsai and Yeung (2020) investigate how mobile-payment channels can positively impact the economy when used as a substitute for cash.

Background and empirical design

In April 2017, DBS – Singapore’s largest bank – rolled out Quick Response (QR) code technology for mobile payments, which allowed consumers to make transactions or transfer funds by displaying or scanning QR codes on their mobile devices. Soon after, in July that year, the Association of Banks in Singapore introduced “PayNow” to enable inter-bank transfers, which, in turn, further facilitated consumers’ payment to businesses.

Unlike credit cards, which could charge merchants transaction fees between 2% – 3%, mobile payments typically do not attract any transaction costs. Given this competitive advantage over other e-payment channels and also the convenience it entails for consumers, Agarwal et al. therefore hypothesised that business-to-consumer (B2C) sectors would respond significantly to mobile payments, and identified these businesses as the treatment group. B2C industries are those that provide goods or services directly to retail customers, and include the retail trade, F&B services, education, health, entertainment and other personal/household services. Business-to-business (B2B) industries, on the other hand, were expected to remain indifferent, and thus served as the control group.

With April 2017 defined as the treatment month, the researchers analysed business registry data maintained by the Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority (ACRA) over the period January 2016 to April 2018 (the sample period). Since all forms of businesses must be registered with ACRA at the time of inception, the researchers therefore had data that encompassed the entire population of firms created in Singapore, including those from the informal sector, such as stallholders and hawkers.

Agarwal et al. also obtained a random, representative sample of 250,000 individuals extracted from DBS’ massive database of retail customers representing more than 80% of Singapore’s population. The consumption behaviours and financial transactions of this group over the sample period could corroborate and explain business behaviours, and also furnish evidence that mobile payments were actually used as a substitute for cash.

Findings

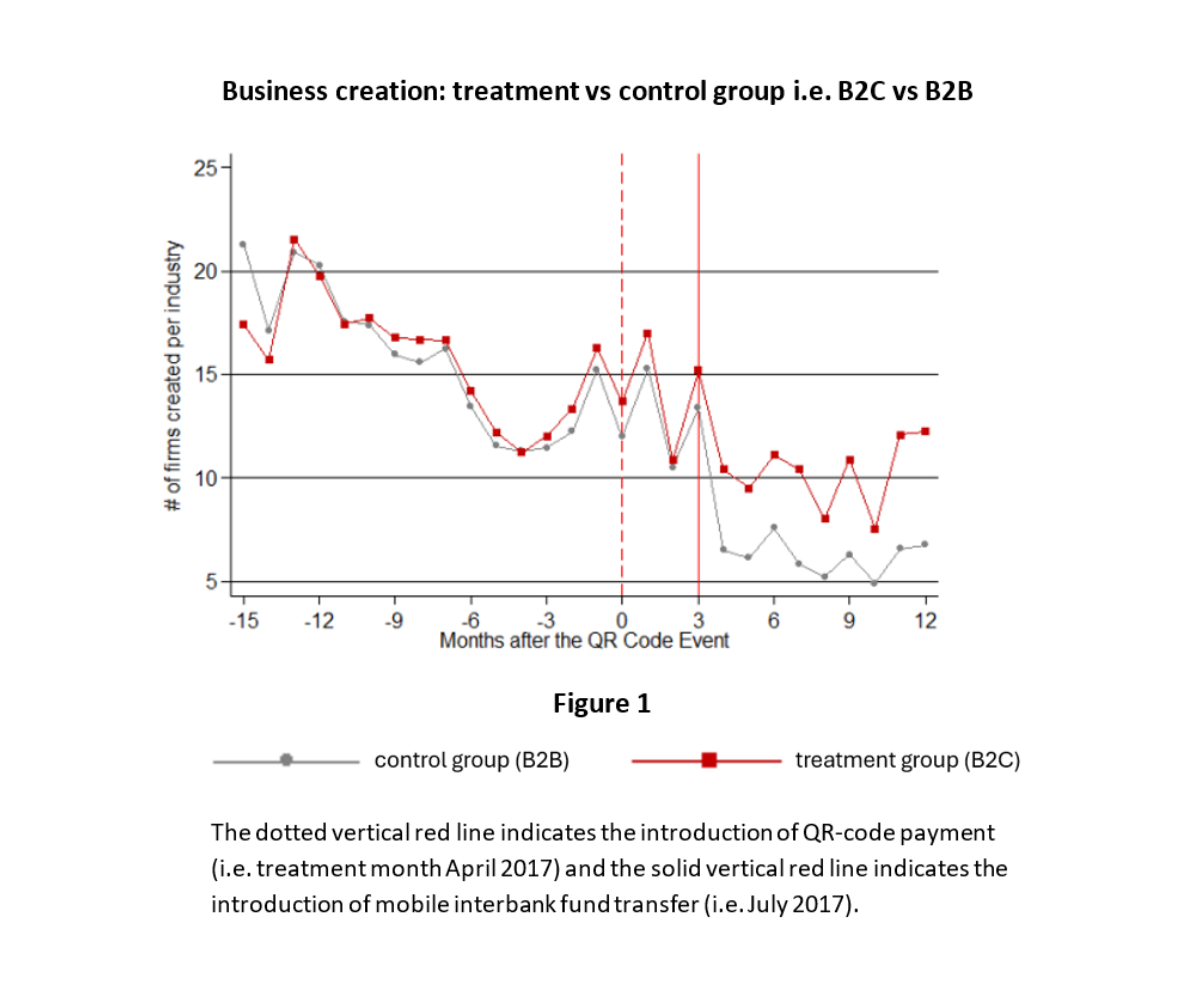

For the 9 months prior to the treatment month (i.e. July 2016 – March 2017), the difference between business creation in the treatment and control group were statistically insignificant and economically trivial (Figure 1).

Both groups closely tracking each other over an extended period of time supports the parallel trends assumption, which in turn supports a differences-in-differences analysis. In the absence of treatment (or any other exogenous shock), both B2C and B2B industries are expected to maintain this “parallel trend” indefinitely. Hence, any deviation from this pattern following treatment – either convergence or divergence – could thus be considered as arising from the treatment. The additional difference on top of pre-existing differences constituted the treatment effect.

Immediately following treatment, business creation rates in the treatment and control groups began to diverge (from month 0 onwards in Figure 1). Business creation among B2C industries increased by a statistically significant average of 8.9% per month more than B2B industries, relative to the pre-shock period. Given a monthly average of 1,478 B2C firms created pre-shock, the implementation of mobile payment technologies incrementally raised the B2C creation rate by 132 per month (= 1,487 x 0.089).

The researchers further observed that small businesses – defined as sole proprietorships or partnerships as opposed to corporations – were driving the change. Being more sensitive and vulnerable to cost, these firms were expected to exhibit a stronger response to mobile payments. Findings from the study showed that the number of small businesses created among the treated industries grew by 12.3% per month after the introduction of mobile payments, relative to the control group.

Consumer response

After segregating the DBS sample of bank customers into a treatment group comprising people who were receptive to mobile payment technology and a control group comprising those who were indifferent, Agarwal et al. found that treated consumers increased their mobile payment amount by a significant 25.4% relative to the control group after April 2017.

The researchers estimated the percentage increase to amount to an average of about S$222,000 per month for the sample under study, or equivalently, an economically significant S$4.5 million per month when extrapolated to the entire DBS population of retail-banking customers.

The treatment group also decreased their cash withdrawal amount by 2.7% afterward, which was mainly associated with the reduction in ATM cash withdrawal. These findings were consistent with mobile payments substituting for cash transactions, reducing transaction costs, raising consumer spending, and thus encouraging business entries.

In summary, after widespread implementation of mobile payment, consumers exhibited a higher propensity to consume, and also took advantage of its convenience to substitute for cash.

Policy implications

In their study, Agarwal et al. estimated cash usage to account for 43% of total monthly spending in 2016. This figure ought to be considerably lower by now, as the 2022 Statista figures shown above would suggest. Yet, in so far as mobile payments continue to raise the consumer’s propensity to consume and encourage business creation, cash usage continues to impose an opportunity cost on the economy.

Policymaking in this area could delve further into ways to support the unbanked minority, and how to help seniors transit into the e-payment ecosystem.

Agarwal, Sumit is the Low Tuck Kwong Distinguished Professor at the School of Business and Professor in the departments of Economics, Finance and Real Estate at the National University of Singapore.

Qian, Wenlan is the Ng Teng Fong Chair Professor in Real Estate and Professor of Finance and Real Estate at the NUS Business School.

Ren, Yuan is an assistant professor at School of Economics, Zhejiang University.

Tsai, Hsin-Tien is an assistant professor at Department of Economics, National University of Singapore

Yeung, Bernard is the Stephen Riady Distinguished Professor in Finance and Strategic Management at the National University of Singapore Business School.