Government cash transfers and the housing market – a case study of the US

Lin Leming’s working paper examines how large-scale direct government payments during COVID-19 enabled more Americans to buy homes, improve their living conditions, and helped fuel a historic boom in the US housing market.

Wong Wei Chen

25 August 2025

How would needy households respond to government cash transfers?

Intuitively, one would expect recipients to use the extra money to pay bills, buy groceries, cover rent or other short-term debt obligations, and perhaps even purchase a spanking new TV or some other durable household item.

And often, common sense prevails. Research has shown that direct cash transfers are indeed frequently spent on immediate consumption. For example, a study by Agarwal, Qian, Ruan and Yeung found that retirees who received cash transfers under Singapore’s Silver Support Scheme increased their total spending by 0.73 dollars for every dollar of subsidy received.1

Those seniors expanded their geographic footprint, visiting more places than usual, increased the variety of their purchases, and raised their food spending, including eating out more often. The government transfers had encouraged these otherwise frugal individuals to indulge a little more than usual.

Lin Leming’s (2025) working paper “Fiscal Stimulus Payments, Housing Demand, and House Price Inflation”, however, uncovered something rather unexpected. During the COVID-19 pandemic – a period marked by severe economic turmoil over 2020 and 2021 – the US government rolled out fiscal stimulus programmes, delivering a staggering US$900 billion in cash payments to vulnerable households to help them weather the crisis.

The injection of cash had apparently created a wealth effect among the lower-income households that eventually motivated renters to buy their own homes or existing homeowners to upgrade to bigger premises. As Lin noted in his study, the pandemic period lasting over 2020 and 2021 witnessed an unprecedented housing boom that even eclipsed the housing growth rates leading up to the 2008 financial crisis.

As much literature in the field had been focused on how government transfers had raised short-term consumption in households, Lin’s finding is not immediately obvious – and is, in this regard, a nontrivial discovery.

The supporting evidence

After the stimulus, the homeownership rate of the bottom quintile increased by a statistically significant 2.2 percentage points relative to the top quintile (i.e. bottom and top 20% of households respectively). Most top-quintile households – except for a minority at the lower bracket – were too affluent to qualify for transfers and were thus used as a benchmark or control to measure the impact of the transfers.

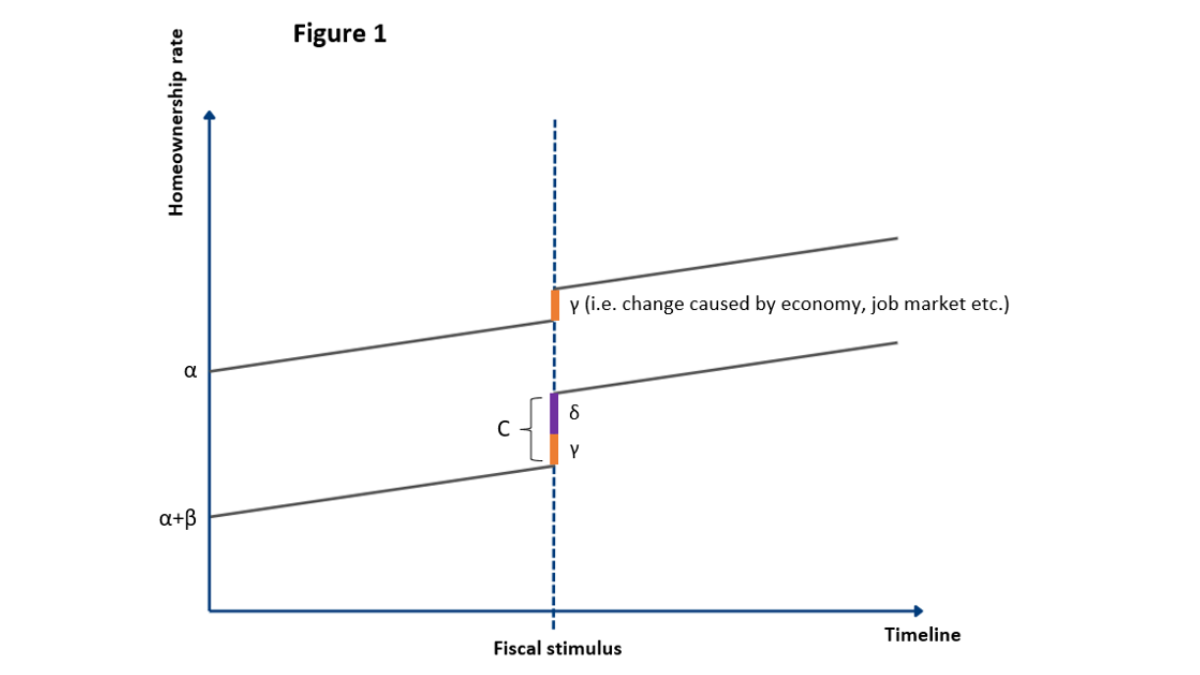

The underlying logic is that since the benchmark group did not benefit from the fiscal stimulus, it represented a counterfactual scenario where no transfer programmes were rolled out. Therefore, any change exhibited by this group before and after policy implementation could reasonably be attributed to exogenous factors – for example, broader economic conditions, changes in interest rates, or shifts in the job market – and these effects are expected to apply across all income groups.

Following the difference-in-differences methodology, any shift in the top quintile was therefore subtracted from homeownership changes observed in other quintiles after policy implementation, and the remaining balance can thereafter be interpreted as arising from the causal impact of the fiscal stimulus. (See Figure 1 below for a simple illustration of this concept.)

The next three quintiles above the lowest quintile respectively saw statistically significant increases of 1.5, 0.8, and 0.4 percentage points in homeownership rates. This pattern is not surprising, since the cash transfers represented a much larger boost to income and savings for lower-income households than for those higher up the income ladder.

An eligible household with two adults and two children could receive up to US$11,400 in Economic Impact Payments (EIPs) and an additional US$6,000 to US$7,200 in Child Tax Credit (CTC) payments – both key components of the pandemic fiscal stimulus programme. These amounts are substantial for lower-income families, considering that the median American household had only US$26,000 in non-retirement financial assets including deposits, bonds and stocks, according to a 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances. The robust income boost was significant in helping families make home downpayments, which they would otherwise have been hard pressed to fork out.

Lin’s analysis also showed that many existing homeowners in the two lowest income quintiles took the opportunity to upgrade to larger premises. Among homeowners, the lowest quintile saw an average increase of 0.041 rooms per person, while the second lowest quintile experienced an increase of 0.023 rooms per person – and both were statistically significant gains. In contrast, renters showed no discernible change in housing consumption, suggesting that the most substantial improvements in living space were driven by those able to transition into homeownership or to purchase larger homes.

Why not supply and demand?

In addition to good evidence, a robust explanation ought also to address (and systematically rule out) alternative explanations that could be equally plausible. In Lin’s study, this entails testing whether factors like supply shortages, migration patterns, remote work, or broader economic trends could be behind the housing boom.

In Singapore and across much of Southeast Asia, the COVID-19 pandemic caused massive supply chain disruptions that acutely constricted the supply of new housing. Over time, pent-up demand here drove home prices up, triggering the Singapore government to raise Additional Buyer’s Stamp Duty (ABSD) rates in December 2021 to reign in investors seeking multiple homes.

But was the US housing boom during the same period simply the result of a similar supply crunch? Or was something else at work?

Lin’s study found that housing supply in the US actually climbed during the pandemic years, averaging out at an annual 2.4% growth, compared to an annual average of 1% from 2017 to 2019 and 0.9% from 2015 to 2017. In fact, some metro areas with the fastest housing supply growth – like Austin in Texas, Provo in Utah and The Villages in Florida – also saw some of the sharpest price increases. This evidence points away from a "supply crunch" explanation and towards a powerful demand shock as the main driver.

Even after taking into account other variables like migration flows, population changes, remote work, and local credit conditions, Lin finds that the relationship between fiscal stimulus payments and house price growth remains strong and statistically significant. In regions where more residents received larger cash transfers, house prices and homeownership rates rose the most, even after adjusting for all these other influences.

The regression kink – proving causality

Beyond demonstrating correlations, Lin’s empirical design relies on a “regression kink” approach that compares households at the margin of the stimulus payment eligibility threshold. Individuals earning less than US$75,000 (or equivalently, couples earning less than US$150,000) qualified for the full payment. Above these thresholds, the payments gradually phased out, reaching zero at higher incomes (e.g. at US$99,000 for single filers in the first round of payments under the CARES Act in March 2020).

The prediction is that those just below the threshold (who received the full stimulus) would be more likely to buy a home or upgrade to better housing, while those above the cutoff (who received reduced or no payments) would show a progressively smaller tendency to do so. In other words, if the stimulus payments mattered, there should be a clear drop – or “kink” – in the probability of homeownership and housing consumption right at the eligibility threshold. (See Figure 2 below, reproduced from Lin’s paper.)

Lin’s findings corroborate this prediction. For example, among married couples with no children, moving from the threshold income of $150,000 (full stimulus payment) to $160,000 (lower stimulus payment) is associated with a 0.8 to 1.9 percentage point decrease in homeownership and a 0.03 to 0.05 reduction in rooms per person.

As further corroboration, Lin shows that this kink is not observed in the years before the pandemic, nor does it appear when the analysis is repeated at artificially constructed income thresholds (such as shifting the cutoff from US$150,000 per couple to higher or lower values). This reinforces that the observed effect is unique to the stimulus payment eligibility rules during COVID-19.

Policy implications

The impact of the American fiscal stimulus programme on housing consumption during COVID-19 suggests that cash transfers of sufficient size can spur households towards major decisions such as homeownership.

While small transfers catalyse daily consumption behaviours, big payments can drive wider changes in the economy such as the housing market. Lin’s evidence suggests that, along Keynesian lines, government intervention can powerfully stimulate demand when it is most needed. But the findings also highlight the need for caution: such interventions, if not carefully calibrated, can fuel rapid house price growth and broader inflation.

Lin, Leming is an associate professor of business administration at the Katz Graduate School of Business, University of Pittsburgh.

1. Agarwal, S., Qian, W., Ruan, T., & Yeung, B. Y. (2025). Supporting Seniors: How Low-Income Elderly Individuals Respond to a Retirement Support Program. Available at SSRN 3611637.